15 Dropped Balls: a Post-Mortem of the UK's COVID-19 Response

Introduction to Biosecurity Series - Part VI

This article was written as part of a period of self-teaching and was used to facilitate my learning. I can’t promise it’s insightful, original, or even accurate. However, I can promise that my next article will be a little better.

____________________________________________________________________________

The UK’s COVID-19 response was poor. There is a fair bit of consensus here and I will attempt to explain precisely why this was the case.

Some caveats about this article, however:

This article is not a comparative account of the UK’s response compared to other countries. For the most part, I’m attempting to recount the UK’s failings in absolute terms. This means that all of the below lack important global context. Many of the challenges outlined were similarly faced by the wider global community or, in part, caused by pressures in the global COVID-19 landscape.

I defer to a number of reports throughout this article, but I make no assurances that the contents of these articles are necessarily accurate. This isn’t an independent research project - it’s an attempt to picture why so many bodies and reports have independently found that the UK’s COVID-19 response was lacking.

However, all factual errors and simplifications remain my own.

This will be the penultimate article in the Introduction to Biosecurity Series before I dive deeper into specific elements of biorisk and solutions. It represents a synthesis of my understanding of biorisk, biosecurity solutions, and what happens when things go wrong so far. Putting this together has been incredibly insightful, and I hope it’s equally as helpful for readers.

1. The State of Play

SARS-CoV-2, responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, is a novel coronavirus that emerged in late 2019 in Wuhan, China. It belongs to the same family of viruses as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, which caused the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreaks, respectively. SARS-CoV-2 primarily spreads through respiratory droplets, leading to symptoms ranging from mild cold-like manifestations to severe respiratory distress, organ failure, and death.

SARS-CoV-2 is a highly transmissible and pathogenic coronavirus that causes COVID-19, a disease characterised by a wide range of flu-like symptoms, from mild to severe. The virus has a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome, and its spike protein plays a crucial role in binding to the human ACE2 receptor - found throughout the human body - then entering host cells. It is extremely transmissible, spreading primarily through respiratory droplets, aerosols, and contaminated surfaces. The virus's ability to mutate has led to the emergence of multiple variants with potential implications for vaccine efficacy and public health measures.

However, before we even tell the story of its emergence in the UK in 2020, many of the UK government’s errors in dealing with the pandemic were due to poor pandemic preparedness that dates many years before. It is decades before 2020 that our story begins.

Failure Point #1: Poor Risk Assessment

This post-mortem will point to several object-level failures in the UK government’s planning for, and approach to, the COVID-19 pandemic - from mask shortages; failures to adequately test at scale, and conflicting advice concerning non-pharmaceutical interventions. However, it is not like these missteps were total surprises.

The National Audit Office’s report on the government’s preparedness for the COVID-19 pandemic reported that the UK government participated in 282 incident and simulation exercises between 2003 and 2016. The outcomes of these experiments included identifying that the UK could not sufficiently surge resources into key areas and identifying that most of the UK’s pandemic plans did not adequately consider mitigating actions for the loss of suppliers or delivery partners during a pandemic.

However, these tabletop exercises and consequent planning focused on influenza pandemics and ‘emerging high-consequence infectious pathogens’ such as MERS-CoV. Influenza is less transmissible and less virulent than COVID-19, and MERS-CoV, whilst much more fatal, is significantly less transmissible than COVID-19. Thus, the UK did not have a strategy for broader classes of pathogens (let alone novel coronaviruses) - and not for lack of warning.

Underlying the decision not to create a strategy for broader classes of pathogens; the choice not to improve known gaps in the UK’s pandemic response, and many of the object-level missteps during the UK government’s COVID-19 response was poor risk assessment.

It is easy to be coloured by hindsight bias when critiquing the government’s lack of effective risk assessment. However, as the NAO report identifies, failings in the government’s risk assessments were pointed out before the pandemic.

In summary, The Cabinet Office, through its Civil Contingencies Secretariat (CCS), assesses the most severe risks facing the country through the National Security Risk Assessment (NSRA), a classified document that is summarised in a public-facing version called the National Risk Register (NRR). This then forms the basis of the risk management programs of local resilience forums (which set out the likelihood and potential impact of a range of hazards and threats for specific areas of England and Wales), various arms-length bodies, and other government departments.

Some of the flaws in the government’s risk assessments include not sufficiently exploring high-uncertainty risks; inadequately weighting tail risks; failing to explore interdependencies and root causes between different risks, and a lack of understanding of the downstream effects of different risks. It is likely, had the government’s risk assessment been more scope-sensitive, that the government’s identification of risk would include a more representative threat.

Failure Point #2: Ineffective Risk Management and Poor Governance

Of course, the actual risk assessment was not the only failure here. The government did identify a pandemic as the single most significant risk to the UK in 2008. As aforementioned, several reports have been written and pandemic exercises run which identified learnings directly relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Exercise Cygnus, a 3-day exercise on the UK’s response to a serious influenza pandemic, identified that such a scenario would “[outstrip] the capacity of local responders”; requires better multi-agency coordination, and requires much more planning for specific breaking points - from the strategy for deploying antivirals to triaging staff capacity to mitigate excess deaths. The report also recommended a single body - a “Pandemic Concept of Operations” - to coordinate the pandemic response. Unfortunately, not only were many of these measures not implemented in time, but the reports of Exercise Cygnus, and other exercises, were initially not even published.

Why such measures were not implemented, even though the government were well aware of the risks a pandemic could bring, is a complex matter in itself. Electoral incentives; a lack of independence of public health bodies from the government, and ineffective decision-making all play a part. However, the outcome is clear - the UK government possessed the knowledge required to mitigate the number of deaths of a pandemic years in advance and did not act on it.

Failure Point #3: Absence of a Relevant Plan

As a consequence of poor risk assessment and ineffective risk management, the UK government lacked a plan for dealing with COVID-19.

The most developed strategies were the UK Influenza Preparedness Strategy 2011 and the Pandemic Influenza Draft Bill which succeeded Exercise Cygnus and would form the basis of the Coronavirus Act 2020.

Aside from the fact that the Coronavirus Act commenced ~55 days after the first COVID-19 cases in the UK, the lack of applicability to COVID-19 and the failure to implement the recommendations of numerous reports beforehand meant there were simply no plans in place for many of the important strategic considerations for dealing with COVID-19.

As the British Medical Association’s report into the UK’s pandemic preparedness for COVID-19 notes, “the response across the UK was centred around increasing capacity within health and care systems to treat the illness. This was in contrast with countries that had experience of dealing with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) or MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome), where contact tracing, isolation and stockpiling of equipment and consumables were given high priority, as in South Korea.”

This meant there were several holes in the UK’s government strategy. To name a few:

The 2011 plan noted, “there is in fact very little evidence of widespread benefit from [the wearing of facemasks by the public in the community and household setting]”, whilst later studies would begin to demonstrate their efficacy. Thus, there was no strategy for scaling the production and distribution of face masks in the UK at the start of the pandemic.

Neither the 2011 plan nor the 2017 risk register identified a strategy for a national lockdown. Instead, voluntary isolation and the possibility of local authorities implementing quarantines were raised as possible approaches. This led to inconsistent strategies for implementing and enforcing a national lockdown.

There was no prior strategy in place for contact tracing. As the BMA report identifies, this led to early contract tracing efforts being scrapped before the Coronavirus Act 2020 was even in effect as “with additional resources, transmission would reach a rate at which contact tracing would no longer be effective and would then need to be abandoned” - only for contact tracing effort to be resumed and scaled in May.

Strategies for dealing with the wider socioeconomic consequences were not in place, even though these had been modelled in the aforementioned exercises earlier. As the National Audit Office (NAO) report notes, "the government lacked detailed plans for several aspects of its response to COVID-19, including shielding, employment support schemes and managing the disruption to schooling”. This led to schemes such as “Eat Out to Help Out”, which likely led to even more COVID-19 infections albeit with limited positive economic effects.

Failure Point #4: Inadequate Infrastructure

A consequence of a lack of an appropriate pandemic plan and limited execution of plans and learnings that were in place meant public health infrastructure was not geared to deal with COVID-19 sufficiently.

This point is stressed by the BMA report, “Public health systems across the UK entered the pandemic without the resources, workforce, capacity, structures, or voice they needed to shape and influence governmental responses to COVID-19.”

NHS underfunding has been regularly reported for many years in the run-up to the COVID-19 pandemic, from cost pressures and its funding gap to the absence of preparedness for increased cost burdens due to an ageing population. In particular, PHE saw its operational budget cut by 40% between 2013 and 2019.

Whilst the pandemic would see cash injections of billions of pounds to support efforts, this meant that the cash could not be used to effectively implement measures with long lag times - such as increased training and hiring of medical staff to offset staff shortages.

However, the BMA report identifies a number of structural impediments to effective coordination during the pandemic as a consequence of prior legislation, particularly the Health and Social Care Act 2012 - which transferred public health functions from regional primary care trusts (PCTs) and strategic health authorities (SHAs) to the newly-created Public Health England (PHE), and instead newly-created clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) would operate locally with a greater focus on primary care.

For example:

The separation of public health into Local Authorities and PHE meant that many public health consultants and teams in Local Authorities became deskilled in health protection work

Doctors reported that a disconnect between PHE and local directors of public health potentially led to the lack of capacity to “[locally] implement [centralised] plans nor the knowledge and expertise centrally to advise on what is necessary for a local population.”

Local authorities did not have access to centralised public health data quickly enough. Additionally, data would often come from various sources on different dashboards, making it challenging to piece together.

Additionally, as the Public Accounts Committee 2020 report into the UK’s pandemic preparedness notes, “there were no support schemes for businesses and individuals “on the shelf”, there was a delay in implementing the schemes as they needed to be designed from scratch”. The NAO report also notes that Brexit meant the Civil Contingencies Secretariat - responsible for emergency planning in the UK - “allocated 56 of its 94 full-time equivalent staff to prepare for potential disruptions from a no-deal exit, limiting its ability to focus on other risk and contingency planning at the same time.”

The most obvious example of a lack of infrastructural readiness was the absence of a dedicated pandemic response unit until the pandemic had already set foot in the UK, and the absence of a prior strategy for delegating elements of the COVID-19 response to the appropriate level of authority. This led to inefficient decentralisation (e.g. concerning procurement) and inefficient centralisation (e.g. test-and-trace).

Given the lack of readiness for the COVID-19 pandemic, it is unsurprising that there were so many eventual missteps once it had arrived on the shores of the UK.

2. The Fight Against COVID-19

On the evening of January 29th, two paramedics responded to a mother and son experiencing fever, cough and a sore throat. Two days later, they would be the first individuals in the UK to be diagnosed with COVID-19. Yet, at the point this first diagnosis was made, a serious error had already been made with respect to the government’s fight against COVID-19.

Failure Point #5: Not-so-Early Detection

By March 23rd - the start of the first national lockdown - the official case count was 6,650. However, research shows that hundreds of thousands of COVID-19 infections had likely occurred in the UK by this time - i.e. only around 1% of infections were being detected and reported.

COVID-19 was first detected in December 2019. However, it was detected in response to patients experiencing pneumonia-like symptoms in Wuhan, China. Given roughly 40% of those who had COVID-19 were asymptomatic, let alone had a mild case, it is extremely unlikely these represented the first actual cases of COVID-19. The fact that antibody studies suggested the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States in December 2019 lends credence to this suggestion.

In turn, COVID-19 was potentially already a pandemic before it was even noticed. The failures of early detection were certainly not limited to the UK. Public Health England did (and still does) possess an extensive surveillance system. However, it is primarily based on clinical diagnostics. Particularly for a pandemic with high levels of asymptomatic transition, waiting for a sufficiently sick patient to self-report or be admitted to a hospital means by the time the UK government was ready to launch COVID-19 countermeasures, it had already spread widely.

Failure Point #6: Slowness to Act

The early stages of the pandemic were rife with uncertainty. However, this uncertainty meant whilst the UK government were aware of COVID-19’s presence in the UK by January - and had already advised travel to China - the Coronavirus Act 2020 was not in force until late March 2020.

Thus, even whilst the gravity of COVID-19s potential to spread rapidly was well understood, and the virus was rapidly spreading in Italy in February 2020, the UK mostly resorted to contact tracing.

The causes of this delay are also complex and naturally involve factors ranging from scientific uncertainty about the nature of this novel coronavirus to political incentives. However, whilst this article does not attempt to provide a comparative picture of the UK’s response, one should note that Singapore - which detected its first case roughly a week before the UK - began implementing a suite of measures by February 3rd.

One should also note that the 2011 Influenza strategy notes that “the indicator for moving from [the assessment stage to the treatment stage] would be evidence of sustained community transmission of the virus, i.e. cases not linked to any known or previously identified cases.” This was likely reflected in the decision to move the UK from a “containment” to “delay” strategy on March 3rd. The first new national rules - i.e. the first lockdown - were announced nearly three weeks later.

Thus, it is likely that institutional risk tolerance and collective judgement played some part in the delayed response.

Failure Point #7: Limited Testing and Contact Tracing

Connected to a lack of early detection was insufficient testing throughout the pandemic.

Much has been written about the sheer lack of testing capacity throughout the early stages of the pandemic. For example, roughly ~10,000 swabs were processed a day by March 23rd 2020 even though, as previously stated, hundreds of thousands of individuals likely had COVID-19. This lack of capacity led to the government’s decision to pause community testing - only for this policy to be reversed in May. Thus, it took until September 2020 for the COVID-19 app to be launched, by which point there were 3000 new cases a day.

As this House of Commons Briefing Paper into COVID-19 testing identified, the cause of this issue we due to several factors, including underutilised lab space; the short supply of reagants required for COVID-19 testing kits, and logistical challenges (including a lack of cargo space given planes were grounded).

Not least, the BMA report noted that the outsourcing of test-and-trace to external organisations led to inadequately trained staff and insufficient data-sharing. The upshot of this was the inefficacy of self-isolation as a countermeasure against COVID, with low rates of individuals being advised to self-isolate and potentially very low (10- 59%) rates of adherence.

Failure Point #8: Poor Mask Guidance

As previously noted, the UK’s 2011 strategy noted that “there is in fact very little evidence of widespread benefit from [the wearing of facemasks by the public in the community and household setting. This seemingly underlined the UK’s initial masking strategy in March 2020, where masks were recommended for health and social care settings but were not initially recommended for use by the general public. As the BMA report notes, “it took until June 2020 for England and Scotland, followed by Northern Ireland and Wales in July 2020, to begin to mandate mask-wearing by members of the public in any setting at all.”

Later studies would confirm the findings that face masks did reduce the prevalence of COVID-19 in the UK. However, as aforementioned, this was not necessarily a new finding. Thus, the delay in mandating masking led to unnecessary deaths and decreased confidence in the government’s mandates.

Failure Point #9: PPE Shortages

Part of the aforementioned structural failings, as this 2020 NAO report into the supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) during the COVID-19 pandemic found, were inadequate stockpiles of PPE due to the government planning for an influenza pandemic rather than anticipating a novel coronavirus.

However, the government further faced distribution problems and a lack of information on local requirements; only developed a full estimate of national PPE requirements between March and mid-April, and then faced long time lags between ordering PPE and it being available to use. The UK government was also constrained by global PPE shortages, lengthening lag times even further.

Large amounts of money were spent on PPE (e.g. between February and July 2020, the Department of Health and Social Care spent £12.5 billion on 32 billion PPE items), however, this ended up often being too late, with complaints of poor communication and inefficient allocation. This NAO report identifies “126 deaths and 8,152 diagnosed cases of COVID-19 among health and care workers as being linked to occupational exposure.”

Failure Point #10: Poor Handling of Lockdowns

Lots of ink has been spilt about how the government handled the COVID-19 lockdown to little consensus. However, two key clear failings were (i) the delay in imposing a lockdown at the start and (ii) the lack of preparation for successive waves of COVID-19 after the first lockdown.

As aforementioned, there was a lag time of roughly seven weeks between the first cases of COVID-19 and the first national measures. One study found that “introducing measures one week earlier would have reduced by 74% the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in England by June 1st, resulting in approximately 21,000 fewer hospital deaths and 34,000 fewer total deaths; the required time spent in full lockdown could also have been halved, from 69 to 35 days. Acting two weeks earlier would have reduced cases by 93%, resulting in between 26,000 and 43,000 fewer deaths.”

On (ii) the lack of preparation for successive waves of COVID-19, the aforementioned BMA report lays this out succinctly. For example, during the summer of 2020 when cases dipped, the UK government:

Developed Eat Out to Help Out, which, as aforementioned, at best had mixed consequences and may have driven new COVID-19 infections up by between 8 and 17%.

Did not build a functional test and trace system (as aforementioned, the NHS COVID-19 app would be launched in September).

Introduced localised lockdowns as cases began to rise rather than presenting an updated national strategy.

The resume of contact tracing via a high-cost model with many outsourced components, which as discussed, led to many inefficiencies.

In turn, the second wave would result in the UK's deadliest day of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Failure Point #11: Ineffective Border Policy

Throughout the pandemic, the government also likely made the following missteps on its border policies.

Primarily, as this Home Affairs Select Committee report notes, the government was correct to adopt an incremental approach to restrict travel to and from countries with high incidences of COVID-19. Many other European countries adopted this approach. However, these measures came in too late. Whilst SAGE identified that border closures wouldn’t necessarily have been beneficial towards the start of the pandemic, other measures such as quarantining arrivals likely would have been beneficial.

Additionally, this report identifies that “failure to advise people travelling or returning from Spain in particular to self-isolate for 14 days (in line with category 1) or, at the very least, to monitor symptoms and call NHS 111 (in line with category 2) was a mistake”, and a lack of clear structure for the monitoring and assessment of emerging infection threats from different countries.

Many more missteps are identified in this report, including but not limited to not having any special border measures for Spanish and French arrivals in May 2020; lifting border measures in mid-March; increased screening for arrivals, and insufficient data collection.

The upshot of an ineffective border policy is the continued entry of the pandemic into the UK’s borders, undermining domestic countermeasures and risking new waves - particularly of variants.

3. Key Throughlines

As the government continued to tackle COVID-19, and the number of these missteps increased, it became apparent that there were fundamental throughlines in the government’s response - key issues and consequences that underpinned every error made. This section will focus on four important ones - the difficulty of executing policy; communication failures; losing public trust, and the existence of perverse incentives.

Failure Point #12: Policy Execution Failures

Policy is difficult, pandemics have wide-ranging consequences, and a lack of preparation meant the UK government was tasked with designing policies on everything from revised examination regulations for students and quarantine measures for care homes to support for NHS staff. Severe resource constraints and time pressures led to a number of policy execution errors.

One such example is the quick roll-out of wide-ranging COVID-19 support schemes likely led to up to £20 billion being lost due to error and fraud. Procurement errors included £4 billion of unusable PPE bought in the first year of the pandemic and the revelation that the UK government unlawfully did not publish Contract Award Notices to organisations that received PPE contracts, often without any competitive tendering leading to billions spent on PPE with inflated prices.

An important case study here is a series of policy missteps concerning social care, including the rapid discharge of people from hospitals to care homes without adequate testing, noted in the Health and Social Care, and Science and Technology Committees’ lessons learned report, as well as excess deaths due to the neglect of care homes and medical professionals themselves not being sufficiently protected - including medical professionals often having to go without the recommended level of PPE in the early stages of the pandemic.

Policy failures in this regard directly led to excess deaths. Still, it is important to note the sheer complexity, resource constraints, and unpredictability of COVID-19 (particularly in the early stages) that would have made effective policy difficult. More effective and thorough preparation before the pandemic was necessary to have prevented these outcomes.

Failure Point #13: Poor Communication

So far, this article has referenced the BMA report on the government’s pandemic preparedness; two NAO reports (here and here) and a Home Affairs Select Committee Report, among others. One thing they all have in common is highlighting a number of communication failures.

Clear communication is important for effective execution; ensuring compliance towards proposed policies, and ensuring public trust. Without effective communication, you risk undermining all your efforts to curtail a pandemic - and it is likely that insufficient and unclear communication played a significant role in limiting the efficacy of the UK’s response.

The reports, in aggregate, are littered with examples:

The BMA reports a lack of communication to public health teams about why decisions were being made centrally on various interventions, resulting in public health teams lacking the insights to apply professional judgement to different situations.

The BMA also reports poor communication between local and national bodies, evidencing Leicester City Council being unaware of which areas would be covered under the local lockdown restrictions until a day before they were implemented.

Public communications were unclear and seemingly confused. This is evidenced by a series of slogans that were nondescript. The BMA notes

“The UK Government’s initial slogan – ‘stay home, protect the NHS, save lives’ – sent an instructive message and left little doubt about what was expected of the public, or why.”

“In May 2020, this was replaced with the opaque ‘stay alert, control the virus, save lives’ which left the public to determine what exactly they should stay alert to and how to control the virus. “

“This was succeeded in September 2020 by ‘hands, face, space’, focusing on hand washing, face coverings, and social distancing, though hinging on public understanding of what exactly this entailed.”

“Ultimately, and potentially reflecting the urgency of the situation and the original slogan’s efficacy, ‘stay home, protect the NHS, save lives’ returned to use in January 2021.”

The NAO report notes that local responders wanted greater access to the government’s pandemic risk assessment and more information on the contingency plans.

The Home Affairs Select Committee report notes the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department for Transport issued contrasting advice to the public about which countries were high-risk.

Ultimately, the upshot of these communication failures were execution errors, low compliance (one in three doctors working in primary care reported hostility from patients or visitors when requesting they wear a face mask), and a lack of public trust.

Failure Point #14: Loss of Public Trust

Public opinion was racked by poor communication, ineffective COVID-19 strategy, and several scandals. Most notable were revelations that Dominic Cummings, then a senior adviser to the Prime Minister, ignored lockdown regulations to travel across the country and that senior members of the UK government held several illegal lockdown parties.

The loss of public trust was demonstrative.

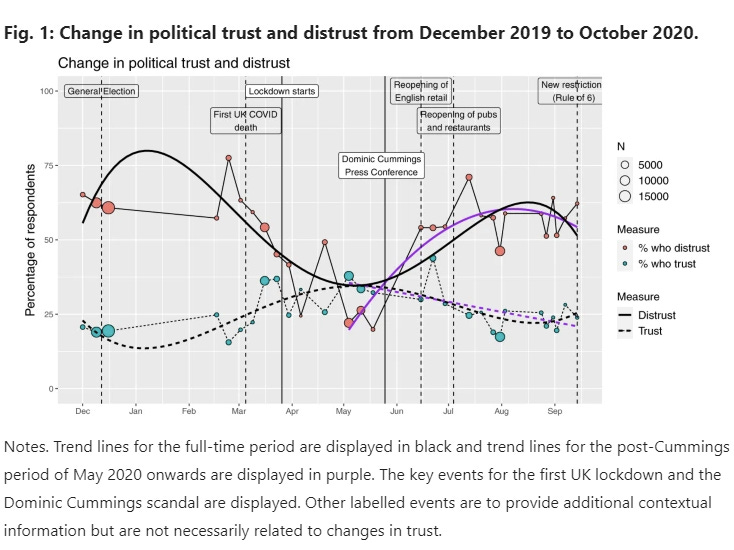

Public trust was very low given the divisive 2019 general election but had begun to increase until the COVID-19 pandemic when the trend would soon reverse. Absolute levels of trust in the government were exceedingly low, with this study finding that by September 2020, only 23% of respondents indicated trust in the government.

Public trust is important for ensuring compliance with government policies and protecting public mental health during the pandemic. Mental health throughout the pandemic remained a severe problem, and structural topic modelling in this study found a lack of confidence in the UK government was in part shaped by the impact of government policies on lockdown.

Failure Point #15: Perverse Incentives

So, why did all even these missteps occur?

This is a difficult question to unpack and requires much more treatment to answer appropriately. However, one would be mistaken to attribute all the failure points to incompetent personnel. Instead, we must recognise that the political landscape did not adequately incentive pandemic preparedness and effective pandemic policy.

One such example is the politicisation of the UK government’s response. By January 2021, nearing the worst of the UK’s COVID-19, 60% of people felt the government was mishandling the pandemic - yet only 29% of conservative voters felt the same. It is unsurprising that we did not see stronger regulations, given many of the steps the government could have taken to reduce infections risked alienating its core economic right-wing vote.

Healthcare was one of the more important issues to the public in the 2019 general election, yet this primarily pertained to general underfunding, understaffing, and poor waiting times. Pandemic risk was not a crux for the general public. Even a year after the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic, neither the Conservative nor Labour party manifestos made any reference to the pandemic or pandemic preparedness more generally.

Finally, as coronavirus measures were underway, the lack of an independent pandemic preparedness body meant there was little accountability was lacking. Both the Chief Executive of Public Health England and its successive body, the UK Health Security Agency, are political appointees - appointed by the UK government. Thus, they are only accountable insofar as the UK government is accountable to the public and captured by pre-existing electoral incentives.

It would have been extremely difficult for any party leader to advocate for effective pandemic preparedness when doing so was not on the public’s agenda; the support of one’s electoral base is relatively insensitive to your execution of the pandemic, and all the bodies positioned to effect appropriate COVID-19 countermeasures are captured by these precise same incentives.

These are also only a few ways the institutional arrangement did not lend itself well to effective COVID-19 governance. As aforementioned, the structure of the NHS; inappropriate centralisation of supply chains, and a pre-existing legal set-up did not require competitive tendering for emergency procurement all incentivised the outcomes we eventually saw.

Without ensuring the institutional arrangement appropriately incentivises pandemic preparedness and effective COVID-19 responses, expecting decision-makers to oppose the path of least resistance is a strategy unlikely to work. An essential problem is how - amidst the inevitability of electoral incentives, partisanship, and myopic public opinion we motivate effective long-term thinking and appropriate risk management.

4. The Next Pandemic

So how prepared are we for the next pandemic?

In short, probably not enough.

Several new measures are in place. Namely:

Public Health England was restructured into the UK Health Security Agency, centralising essential health security functions.

ARIA (Advanced Research and Invention Agency) was founded to focus on projects with the potential to produce transformative technological change.

However, many recommendations from reports and exercises - such as a dedicated pandemic response team - have yet to be implemented. The NHS shortfall persists, and the government’s risk planning - which now incorporates the risk of pandemics due to novel coronaviruses - makes no references to other potential sources of biorisk, such as Marburg virus or bioterrorism. Several leading scientists report that the UK remains unprepared for a future pandemic.

One thing the UK did get right was the rapid development and deployment of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines. Work on the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine began in February 2020 - within two weeks of the first UK case of COVID-19. Where vaccine development can take up to a decade, three COVID-19 vaccines were granted emergency-use authorisation (EUA) in the United Kingdom within 11 months after the SARS-CoV-2 sequence was published. On December 8th 2020, Margaret Keenan became the first person in the world (outside trials) to receive her first dose of two of the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Within a year, over 120 million doses had been administered.

Thus, vaccine readiness will likely remain a strong point for future pandemics. However, given the rate at which pathogens can spread, vaccines cannot be the first point of defence. It remains the case that nearly 225,000 people died from the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK.

5. Key Takeaways

This article detailed many - but far from all - of the failings of the UK government’s response to COVID-19. However, it is essential to note that the lesson here is not merely about avoidable failures that UK government personnel made.

In fact, on some indexes, the UK ranked as one of the most resilient countries against COVID-19 in the world:

Number 6 on the Pandemic Resilience Index 2022, updated in November 2021.

Number 22 on the Bloomberg COVID Resilience Ranking 2022, updated in June 2022.

The UK also did very poorly on other indexes and, at 3128 deaths per million, did have one of the worst fates globally. It can not be downplayed that poor decision-making and ineffective preparedness led to excess deaths in the UK.

However, it must be stressed that dealing with pandemics is exceptionally difficult. Almost every single issue outlined above was shared by most countries worldwide. The world was unprepared for COVID-19 and remains unprepared for the next pandemic.

Dealing with a pandemic is a complex coordination problem that requires sufficient foresight and risk management; well-scoped preventative measures across a vast number of domains; cooperation between states, private companies, and local authorities; a solid economic foundation; high levels of adaptability and flexibility to the vicissitudes of a pandemic, and levels of international cooperation that are rare in human history.

The key takeaway is that doing better for the next pandemic - one with a 38% chance of occurring within our lifetime (for a pandemic with a similar impact to COVID-19) - is an exceptionally difficult challenge. However, we must step up to it.

This was really interesting!!